Science Communication is a broad and evolving field that includes diverse encounters of different publics with science or scientific issues.

With a focus on the academic field of science communication (SciComm), partners from IANUS WP2, and especially RU, offer an overview of contemporary approaches to SciComm and a critical analysis of the relation between SciComm and (public) trust in science.

For citizens who are not practicing science as a profession, these encounters with science and scientific issues can happen through a conversation with a friend, an article in the science section of a newspaper, a post in one’s social media feed, a visit to a science museum or volunteering in a local science initiative. However, communicating science to a broader audience is a professional task for scientists, science communicators, and science journalists.

Science communication as a practice and as a discipline has undergone many transformations. These shifts often coincide with shifts regarding the (proper) relation between science and society, so that SciComm tends to respond to and internalize these emerging ideas. The variety of terms used to refer to this concept over time – Public Awareness of Science (PAS), Public Understanding of Science (PUS), Public Engagement with Science (PES), Public Participation in Science and Technology (PP) – reflects this evolving relation between science and society and our shifting understanding of how SciComm is meant to operate.

Although the field and practice of SciComm do evolve over time, prior paradigms tend to persist, meaning that the repertoire of communication modes available to a science communicator expands. Recently, participation as an (equalitarian) process of knowledge co-production appears to be the last manifestation of this process. Yet, with the participation paradigm come challenges, limitations, and failings stemming from pragmatic limitations (such as issues of power and representation) as well as conceptual shortcomings (such as the persistence of scientific framings of the debate)

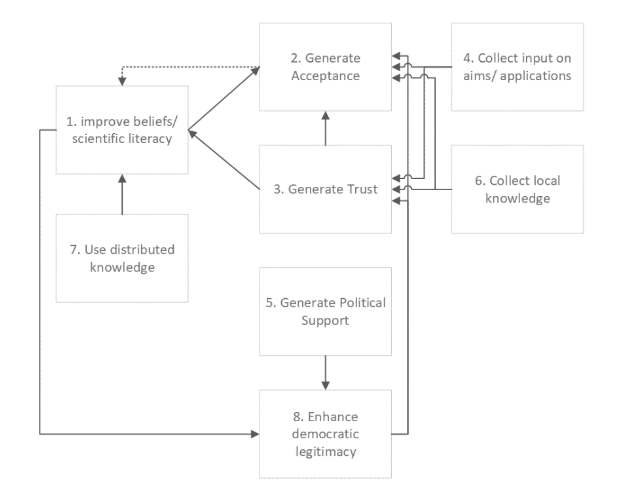

But why do we find it useful to engage in SciComm? Kappel and Holmen (2019), in a conceptual analysis of contemporary SciComm literature, have proposed the following common aims for SciComm:

- Improving the population’s beliefs about science

- Generating social acceptance

- Generating public epistemic and moral trust

- Collect citizens’ input about acceptable/worthwhile research aims and applications of science

- Generating political support for science

- Collect and make use of local knowledge

- Make use of distributed knowledge or cognitive resources to be found in the citizenry

- Enhance the democratic legitimacy of funding, governance, and application of science or specific segments of science

The authors acknowledge that these aims are also likely to coexist, and causal relations between them can exist. Consider, for example, the widespread assumption of the ‘deficit model’ of SciComm, in which information flows from the scientists to the public in an effort to increase scientific literacy and, consequently, support for science. Improving scientific literacy (Aim 1) will generate positive attitudes toward science (Aim 2).

Figure 1 provides WP2’s mapping of the relations as suggested by the authors. This overview shows that aims 2 (acceptance) and 3 (trust) are frequent end aims for other aims.

Figure 1: Assumed causal relations between SciComm aims, drawn from (Kappel and Holmen 2019)

It appears, then, that SciComm is entangled with questions of trust. Firstly, the need to practice or reform SciComm is very often motivated by a perceived lack of trust. The ongoing “credibility crisis” we are experiencing calls for renewed efforts from the scientific community to repair or rebuild trust via (improved and renewed) SciComm initiatives. Secondly, establishing trust is a frequently mentioned objective of SciComm.

It is possible that trust as an objective is only associated with deliberative and participatory modes of SciComm or that SciComm is expected to play a role only when it moves away from the deficit model. At the same time, many argue that trust in science is inexorably related to (traditional) communications about scientific findings or science in general. This is why the rest of IANUS WP2’s work focuses on SciComm as a communication activity between parties. Such an activity can still be interactive or dialogical in form but need not be transformed into a design or decision-making process.

In the following articles, then, we will take a communication science perspective and examine trust in SciComm as a mediated experience. How do trust and SciComm interact with each other as part of a communication process? Which factors may determine whether a SciComm activity is trusted? Second, we will take a theoretical perspective and critically analyze SciComm’s trust claims. We will answer questions such as: what are the theoretical implications of framing SciComm as a trust repair mechanism? What worldview do we (unconsciously) embrace by suggesting a trusted objective for SciComm?

References:

Kappel, K., & Holmen, S. J. (2019). Why science communication, and does it work? A taxonomy of science communication aims and a survey of the empirical evidence. Frontiers in Communication, 55.