In a previous article, we discussed the importance of caring about Science Communication and introduced the notion that SciComm can be understood as a communication activity between parties. When we understand SciComm this way, we can start considering communication-specific predictors of trust, such as features related to the communication medium or to the format of the message. It also reminds us that SciComm operates within a media landscape that is dominated by social media and digital interactions.

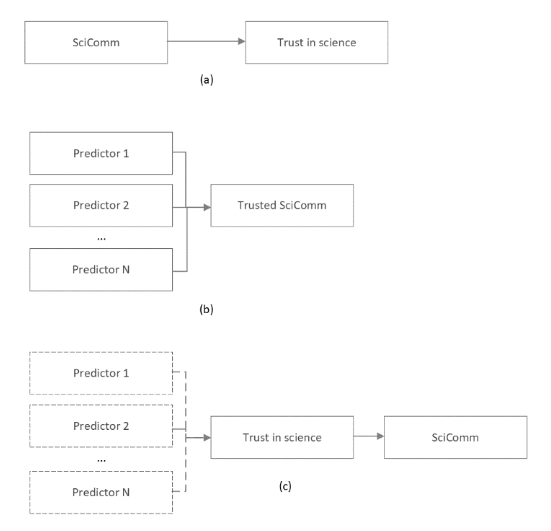

We can thus begin to highlight different relations between SciComm and trust (cf. Figure 2). First, we can observe (causal) connections from SciComm to trust in science: SciComm may foster trust in science; SciComm may be a proxy for trust in science; features of the communication process or its context may affect trust (in the information communicated; in science). Yet, a reverse relation is also possible, i.e., one from trust in science to SciComm. In this case, trust in science can be viewed not only as an outcome of SciComm but also as a factor that, in turn, affects the success of communication. This may hold true for either general trust in science (as a positive disposition towards science) or the trustworthiness of scientists (as communicators).

The figure below helps to envision possible relations between trust and SciComm.

Figure 1: Possible relations between trust and SciComm: (a) Trust in science is an outcome of SciComm: SciComm fosters trust in science or functions as a proxy for trust in science; (b) Specific features of a communication affect whether the communication will be trusted or not (communication-specific trust predictors); (c) Trust in science affects whether a communication will be effective or not (non-communication-specific predictors of trust). Trusted communication = the content of a communication is judged as true, reliable, and sincere.

It appears, then, that effective communication is necessary for any effort to foster public trust in science. In fact, it may even be an obligation if scientists are to be worthy of public trust. To this conclusion, we must also pair a warning: resist the temptation of treating trust as solely the outcome of a well-designed communication. That is because, obviously, the features of a message (e.g., its content, framing, format, channel of delivery…) matter greatly, but fostering trust is not as simple as crafting a proper message. As shown repeatedly, the audiences we hope to reach are complex individuals with their own personalities, values, histories, predispositions, and needs.

Communicators tend to respond to this complex reality with efforts to construct tailored and properly framed messages. Audience segmentation, i.e., the division of an audience into meaningful subgroups, is customary in public communications, such as those about health or climate change. Brossard and Lewenstein (2010) describe such approaches as the ‘contextual mode’ of SciComm and remark that tailored communications while adjusting to the complexities of their respective audiences, still treat people as misinformed subjects to be aligned with an expert opinion. Therefore, SciComm’s efforts to foster trust may suffer from the same desire to ‘correct’ a public’s wrong perception, which in this case would mean correcting audiences regarding trustworthiness.

Yet, trust is relational, so optimizing our messages or communication styles may be secondary to treating our audiences with respect. A true interest in the well-being of those we ask to trust us, a sincere curiosity about what they worry about when they withhold trust, and the willingness to engage, reflect, and take responsibility for our conduct are good places to start.

References

Brossard, D., & Lewenstein, B. V. (2010). A critical appraisal of models of public understanding of science: Using practice to inform theory. In L. Kahlor & P. Stout (Eds.), Communicating science: New agendas in communication (pp. 11–39). Routledge.