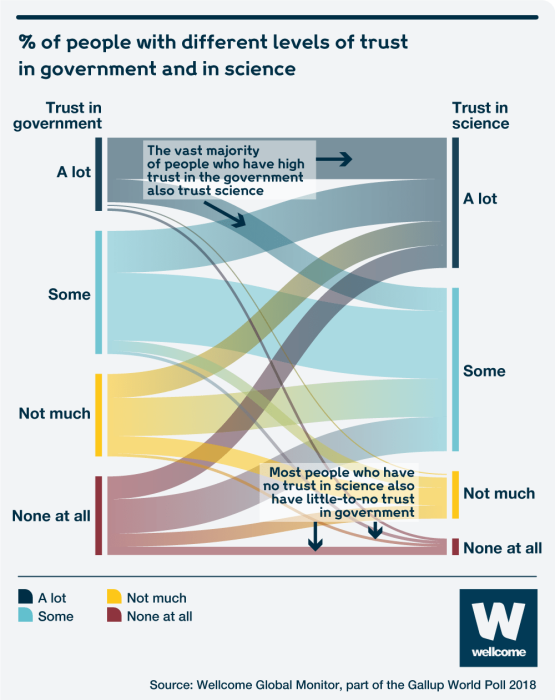

The IANUS project aimed to explore public opinion within the science and technology ecosystem and thus led to the Wellcome Global Monitor, which stands out for its valuable approach. It gauges trust and mistrust by posing specific questions and analysing responses from citizens. Thus, the IANUS team analysed the Wellcome Global Monitor 2018 data, which addressed people’s trust levels regarding science. Trust levels are determined by combining the percentages of those responding that trust “a lot” and trust “some”, while mistrust is represented by those who trust “not much” and “not at all.” This creates a trust index, reflecting the balance of opinion in each EU member state. A positive score indicates more trust than distrust (a trust surplus), while a negative score suggests the opposite (a trust deficit). The magnitude of the surplus or deficit indicates the extent of widespread trust or distrust.

The assessment of public opinion raises the question: is the glass half full or half empty? This question is especially relevant concerning respondents’ opinions of their National Government and Journalists, who often report on scientific matters. Alarming findings reveal that trust in these entities in several EU Member States falls significantly low in the trust index. However, science enjoys substantial trust among over 8 in 10 Europeans. University scientists are perceived as more committed to the public good compared to their corporate counterparts, primarily due to concerns about transparency and conflicts of interest in corporate research.

These findings act as ‘food for thought’ and propose various recommendations for the next research activities of the IANUS team, quoting some of them below:

- Increasing transparency and accessibility of scientific data;

- Measures to safeguard transparency and academic independence;

- Introducing strategies to prevent questionable research practices rather than adopting defensive reputation protection;

- Discourage making extravagant claims in research proposals and with preliminary findings;

- Introduce policies on conflicts of interest;

- Recognise the risks of being used by policymakers to justify their decisions;

- Treat science communication as both dialogical and participatory;

- Avoid treating trust as a public relations exercise;

- View a goal of science communication as enabling participation;

- Learn lessons from public concerns and distrust;

- Acknowledge that while science accepts scepticism, it should not be seen as a problem in the public;

- The risks of metrication recognise Goodhart’s rule: “once a metric is created, behaviour is adjusted”;

- Be aware of the risk of incentives leading to perverse outcomes;