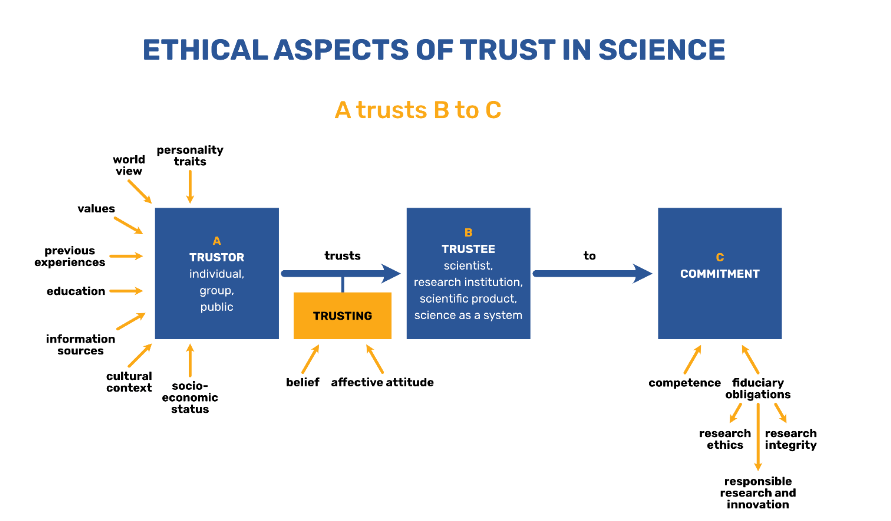

The IANUS researchers have extensively worked to analyse and identify what kind of relationship trust is. Many philosophers seem to lean towards the doxastic view of trust based on the belief that trust functions as a three-place relationship (A trusts B to C; A trusts B to be C). Yet, there’s substantial reasoning to consider that a two-part structure (A trusts B) or even a singular form (A’s trust) may be more foundational.

Trust researchers should distinguish between three different forms of trust: 1) trust; 2) trusting some other person (A trusts B); 3) trusting somebody or something to do something (A trusts B to do C or A trusts B in the role C). The three forms of trust can be explained as follows:

- one-place trust (A’s trust) involves a feeling of confidence and readiness to give up control by refraining from taking precautionary measures;

- two-place trust (A trusts B) entails a feeling of confidence and a positive feeling towards the object of trust, as well as possibly a belief that the trustee is trustworthy, at least in some domains.

- three-place trust (A trusts B to do/to be C) involves, besides a feeling of confidence and positive attitude towards the trustee, also an expectation that C will be able and motivated to fulfil the expectations of A. It is an attitude of hope which involves both a positive feeling towards the object of trust and a belief that the desired outcome is possible or at least not impossible.

Three-place trust (A trusts B to be/to do C) may take the form of either a practical or a moral relationship. In a practical relationship of trust, A has a positive attitude towards B as well as relies on B to do something, arranging her life around the predictive expectation that B will do C. In a moral relationship of trust, A trusts B and relies on B to fulfil C as a moral commitment which she expects her to fulfil. This entails that A believes that B is capable and morally motivated to do C.

There is an important difference between practical and moral relationships of trust. When one relies on the watch to show the right time, the watch does not know anything about their expectations and cannot respond accordingly. In a moral relationship, one treats another person as a moral person (which means to treat another person as an end and not as a means), expecting them to fulfil an obligation that has been mutually agreed upon (either directly or because as members of a moral community they have committed themselves to the same moral norms).

Besides common morality, normative expectations can also stem from the shared norms people relate to certain roles they fulfil, either in their personal relationships (being a mother, daughter, or wife is related to certain obligations) or in their professional life (as an academic working in a university they have roles as a researcher, teacher, supervisor, or leader, all of which are associated with certain commitments). The commitments of professionals are often articulated in professional codes of ethics, which inform the public about what can be expected from a representative of a given profession. Representatives of all professions must fulfil roles they have adopted and perform according to standards, as well as in view of certain values.

By trusting the bus driver, the cook, the teacher or a physician, people know what kind of values and standards the representatives of these professions are committed to follow. Also, the scientists must follow certain values and standards. Being trustworthy means adhering to the commitments related to one’s role or profession.