IANUS researcher Hendrik Berghäuser, from Fraunhofer ISI, created a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework for assessing co-creation methods. They discovered that the concept of co-creation has hardly been problematized in academic literature or thoroughly defined in EU policies. This creates a tendency to regard co-creation as a tick-box exercise of, e.g., including stakeholders, thus neglecting its full potential. To address this, they wanted to advance the knowledge of existing evaluation frameworks or indicators that analyze and assess the impacts of co-creation in various contexts.

Different Evaluation Frameworks for Assessing Co-creation

A thorough exploration of the literature led to a review of the following six frameworks for assessing co-creation:

- Participatory impact pathways analysis (PIPA): This approach focuses on planning, managing, and evaluating projects in complex systems. It usually involves a three-day workshop with key stakeholders in the project to develop pathways expected to achieve defined impacts. This framework is more suitable than “traditional” approaches to evaluate transdisciplinary projects.

- Participatory Impact Assessment & Learning Approach (PIALA): Although similar to the first approach, PIALA claims to be particularly useful when assessing and managing programs or portfolios aiming at systemic changes in complex environments where many often unpredictable interactions and influences occur. This approach usually unfolds in three phases: focusing and framing the evaluation, collecting and linking the data, and analyzing the contributions.

- Social Impact Assessment through Productive Interactions (SIAMPI): This framework is based on the idea that analyzing the processes of research functions as a proxy for impact instead of just measuring the impact of research. This way, societal value is assessed by focusing on interactions between researchers and stakeholders that result in knowledge production and application. This approach examines factors such as the effect of research on society, observable as changes in behavior. However, it does not examine factors such as the quality of life, social security, etc.

- Contribution Mapping: This approach focuses on contributions and processes to avoid overemphasizing impact and knowledge producers. Here, societal value is defined in terms of contributions to actor scenarios to stress that the role and meaning of research outcomes depend on the context of users. The approach focuses on processes and actors and systematically assesses anticipatory efforts that aim to enhance contributions, so-called alignment efforts.

- Payback Framework: This model aims to describe the wider social benefits resulting from providing scientific policy evidence. As a result, the framework emphasizes policymakers as the main recipients of research. To analyze impacts (or ‘paybacks’), various qualitative data sources are acquired through surveys, interviews, and policy documents. The framework entails a seven-stage cyclical model or logic model that represents the complete research process, starting from the inception of a research idea to the final societal outcomes with numerous feedback loops to avoid the suggestion of linearity.

- Socio-Economic Analysis of the Impact of Public Agricultural Research (ASIRPA): evaluates socio-economic impacts through qualitative case studies following a standardized outline of impact pathways in order to enable comparison of the diversity and amplitude of impact. Inspired by actor-network theories of innovation, the approach focuses on the process of impact generation by identifying “the chain of translations”; the sequence of transformations that a research output undergoes to become an innovation.

Moving from Frameworks to Indicators

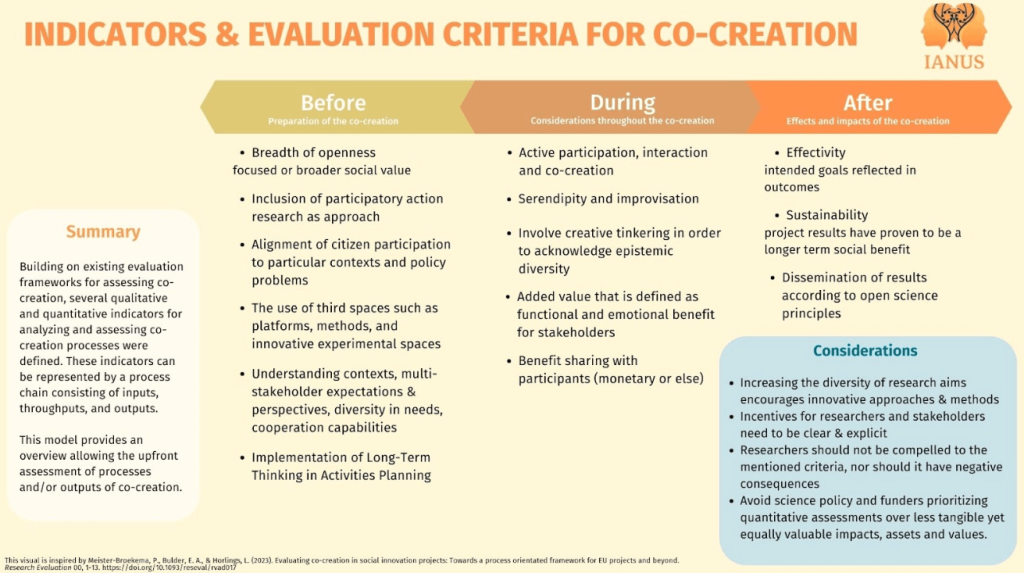

Building on these evaluation frameworks, they revealed several qualitative and quantitative indicators for analyzing and assessing co-creation processes. These indicators can be represented by a process chain focussing on the phases before, during, and after the co-creation activity. Indicators in the first phase define criteria that must be taken into account when defining the research problems and approaches. In the second phase, indicators refer to practices for establishing certain dynamics and shared benefits that should be encouraged throughout the co-creation research process and resulting initiatives. The last phase defines indicators of positive impacts through effectivity and reach.

Considerations

In addition to this model, several strategies must be considered to avoid the misapplication of narrow criteria and indicators for assessing participatory research quality and impact. First, increasing the diversity of research missions and purposes may encourage innovative approaches and methods. Second, incentives for researchers and stakeholders must be clearly and explicitly defined. Third, the above-mentioned criteria must not be forced on researchers, nor should negative consequences be implemented if they are not taken into account. Finally, authors suggest avoiding science policy and funders who favor quantitative assessments at the expense of less tangible but equally valuable qualities, impacts, assets, and values.